An Uninvited Pandemic

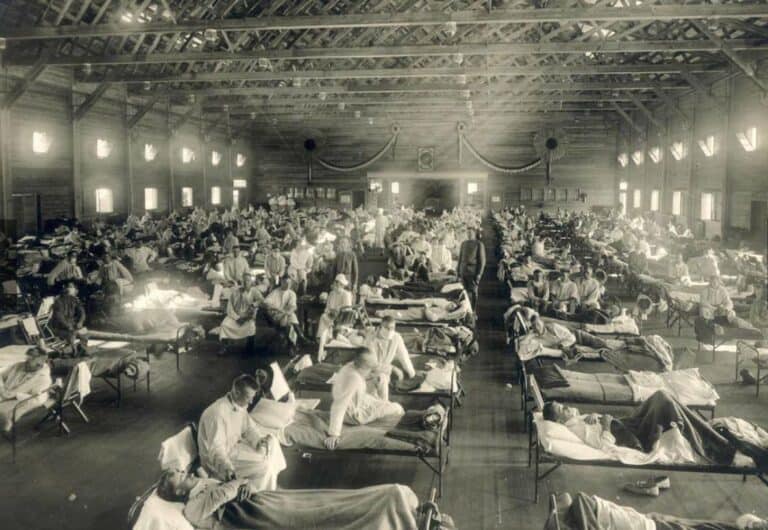

But this flu would not be ignored. Instead, it came gradually, then suddenly. It approached from the back row of issues and rapidly became overwhelming. Millions of people in many parts of the world were impacted. Were scared. Were dying.

This became a devastating Spanish-Flu pandemic in the middle of a World at War.

In May, June, and July of 1918, sickness appeared to be primarily a European problem. But by September, the fast spreading disease had skipped through much of the world. Then, in the hard-hit city of Boston, it attacked with a serious vengeance.

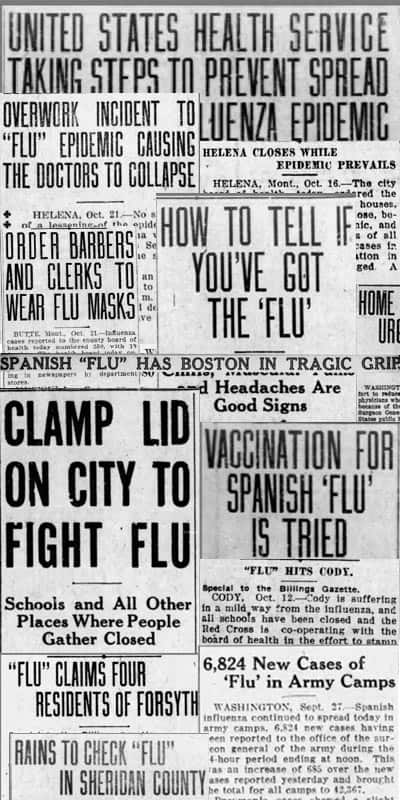

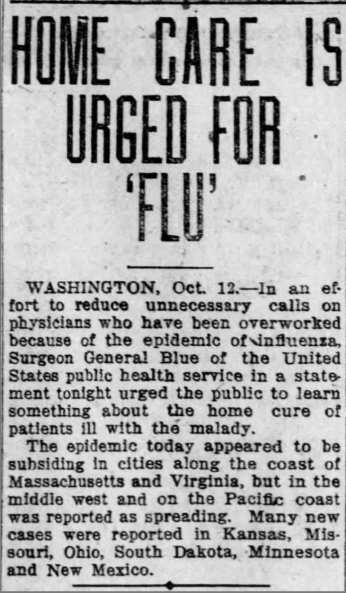

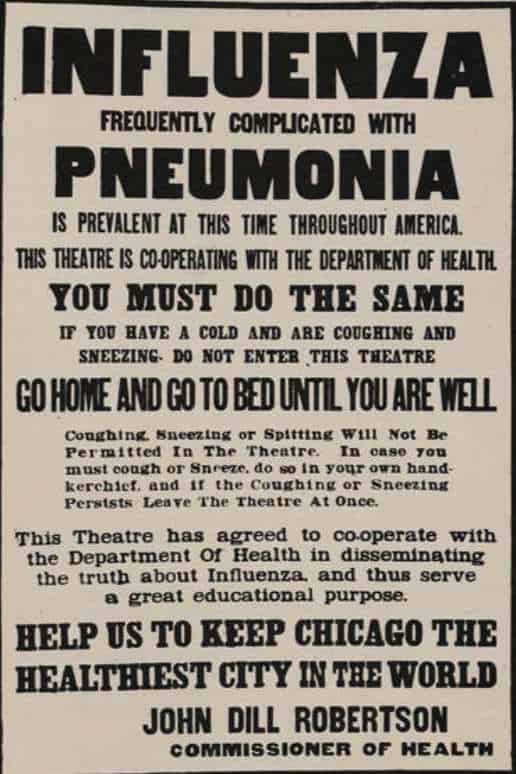

Symptoms, treatments, restrictions, fears, face masks, shutdowns, deaths, conspiracies, blame, shame, political accusations…all of these were similar to other pandemics that would reoccur in future years. Among circulating rumors was that the German Navy had purposely spread disease via their U-Boats. “Cures” were many and ranged from prayer to the novel “kill or cure” treatment offered by Cheyenne Indians. Vaccines were tried with marginal success, but it was not until the 1930s that a virus (not bacterium) was identified as the causal factor.

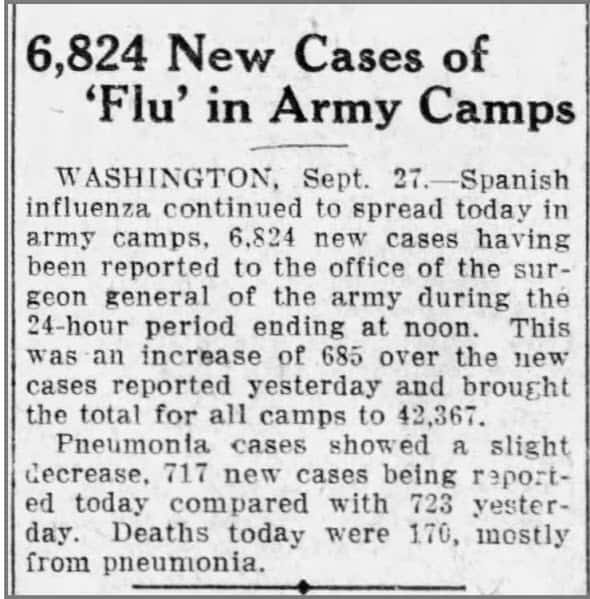

Infections and death were too real not to be taken seriously. Contagion was rampant. Illness was sudden. Deaths were numerous and quick, often within 12 hours. The biggest cities suffered terribly, and our troops were being cut down without enemy bullets. Oddly, the age group most affected was 20 to 40 year-olds, not the very young or old.

Rockwood Brown and his growing family watched with dread and waited as the virus and the silent terror spread. In Montana, regional schools were closed. Businesses were shuttered. Weddings and other public events were disrupted. Helena shut down. Butte recorded a sharp rise in cases, and local restrictions were mandated in all cities.

Lasting from March 1918 through April of 1920, the Spanish-Flu would ultimately infect one-third of the world’s population or 500 million people. Worldwide, the death toll estimates were 30 to 70 million people. In the U.S., at least 850,000 died out of a population of 103 million.

But even though Billings’ raised its alert level and people feared the worst, the city seemed oddly spared. Only 3 deaths out of 377 cases were ever reported. With its head lowered as if to dodge a bullet, the city slowly exhaled with unbelieving relief.

Nationally, the virus had visited every state, and flu deaths had exceeded war deaths. But this pandemic seemed to be expiring on its own and had not been blunted with a vaccine.

World War I officially ended on November 11, 1918, but the flu was still erupting in parts of the country. Celebrations were somewhat tempered. Daily reports on the flu were eventually discontinued, and life slowly resumed.

Back To Business

With the war over, and even before he had a chance to be sent overseas, Grimstad returned to Montana from his training in Pensacola, Florida. Still, he was very happy to be back and immediately found himself juggling legal tasks begun by Brown. He had been gone only nine months, but there were many ventures to oversee, local issues to pursue and…just by the way…a murder trial to start in 30 days.

The number of diverse enterprises…not counting land purchases…that Rockwood started was astounding. One wonders how he could handle law cases and simultaneously be such a vigorous entrepreneur. But he did, and he was.

Rockwood was himself a partial owner, board member, or President of numerous firms: Well Drilling, Automobile Sales, Oil Refining, Gasoline Co-ops, Women’s Shoes, Ranching, Tires, Office Supplies, Agricultural Seeds, Tourism, Coal and Block Ice. No business seemed off-limits.

For a while, the law partnership expanded and became Grimstad, Brown, and Manning. But for reasons unknown, the firm returned to the original partners after two years.

Betting On Oil

In November of 1919, newspapers trumpeted an oil discovery in the nearby town of Roundup, Montana, 50 miles north. Excitement was intense. Brown had lived in Billings long enough to judge the wide-open opportunities that lay before him and his group of investors. One of those opportunities was the future of oil drilling and refining in this emerging industry. So land that had previously been intended for farming, was unexpectedly valuable as possible oil property. He immediately set about to locate oil by acquiring more leases for drilling.

He realized that oil refining factories would also be a necessity, and Billings had the perfect location: 1) It was central to the oil fields, 2) it was nearby a recently completed high-speed rail line, and 3) it had a generous supply of water from the Yellowstone River. So Brown joined with other investors to help promote a new refining company.

Funding Montana's First Refinery

In 1920, a representative of Standard Oil predicted that Montana would someday produce 75% of the total gasoline supply in the United States. This judgment helped add credibility to any investment in Montana’s first oil refinery. The group behind this venture could not yet calculate Montana’s total production, but they were asking for other shareholders to join in the state’s future…albeit with some risk. A large ad in the Billings Gazette solicited other investors for what was essentially an Initial Public Offering.

The three listed officers and directors were attorney Rockwood Brown, Rudolph Molt, on the board of the Montana National Bank, and E. K. Winne, a prominent car dealer, former member of the Iowa State Senate, and President of Hoosier Oil Company. These primary funders as described in the ad were “keen, alert, wide-awake and aggressive” with “unquestioned integrity.” The high profile and believability of all three men helped to bring in capital from 250 individuals throughout the state.

NOTE: The initial investment proved lucrative for Rockwood and his other shareholders when the company was sold in 1922, only two years after its purchase.

Oil production in Montana peaked in 1926. Still, additional refineries were built in the early 1930s in Great Falls, Billings, and Laurel. Newer and deeper drilling methods ultimately made some of Rockwood’s own unprofitable drilling sites into bankable diggings. And during World War II, oil demand was high.

But directors of these ventures did not know that the early euphoria over Montana’s oil discoveries would eventually dissipate. The state would become only modestly ranked in national crude oil production with less than 5 percent of national gasoline production output. Montana today is ranked 14th in state output.