Making It Work

Now Keith was delegated additional responsibilities, the most immediate of which appeared to be turning a profit from powder. It was sink-or-swim.

Other entrepreneurs were already acting to get this mineral to the oil and gas market. A mixture of bentonite and water had been determined to have better coolant, sealant, and suspension properties than the plain water previously used. Deeper and bigger holes required different qualities that bentonite resolved. With seven other companies now selling bentonite, the Brown effort might even have been late to the party. But potential for this mineral seemed too much to discount.

Wyo-Ben’s impetus came from three directions: 1) an increasing world demand, 2) large companies who observed its many industrial uses, and 3) Keith Brown’s drive to make it work.

And one more thing: A popular book of the time even mentioned bentonite, postulating that it could be a kind of “Cosmic Dust” deposited from outer space.

Well, there you go.

Keith theorized that he could probably sell enough of this processed powder to mix with cement for filling vacant oil wells, so he set about to make it a saleable commodity. (A cartoon panel from Dick Tracy even promoted these qualities.)

Meanwhile, the elder Brown had clinched financing for this new venture with  Western Clay Products of Houston. He also secured their first buyer through a company called Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Co., also of Houston. Halliburton would guarantee to buy 90% of the company’s volume.

Western Clay Products of Houston. He also secured their first buyer through a company called Halliburton Oil Well Cementing Co., also of Houston. Halliburton would guarantee to buy 90% of the company’s volume.

Keith then asked Chris Paustian, plant manager of the Stucco gypsum operation near Greybull, to transition that plant to bentonite clay. The fact that the knowledgeable former supervisor accepted was good luck for both men. Paustian was probably the only man that had firsthand experience on how to make such a plant work.

Together they visited a recently shuttered bentonite plant (the only one in Montana) on the Crow Indian Reservation, just a few miles north of the Wyoming state line. Its current owners were instantly open to selling because of their low bentonite reserves and under-capitalization. In fact, the plant had not operated for two years and they were relieved to peddle their unused equipment and be done with it.

Because of its heavy weight, the hundred-mile rail transportation over the Big Horn Mountains was prohibitive. So, from Wyola, Montana, north to Billings and then south to Greybull, Wyoming, Keith sent the used milling facility from one location to the other, mostly by rail. On to Greybull, chugged the two-year-old bentonite equipment, lock, stock, and barrel-kiln.

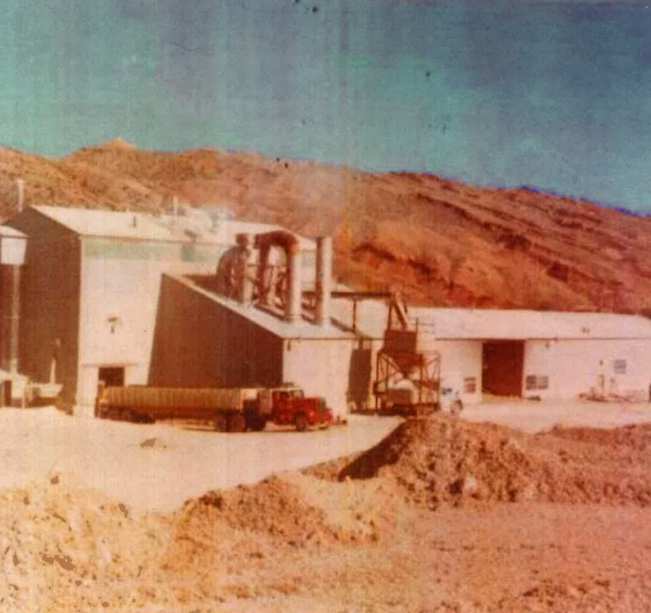

In January of 1952, a scruffy-looking facility employing five people tentatively started its business under the name Wyo-Ben Products Company. But, partly because of sudden competition from larger and better-financed operations, it struggled to be profitable. For lack of funds, promotional opportunities were lost. And almost before it could get its feet on the ground, the small bentonite plant’s financing vanished.

Rockwood Brown and R.E. Dansby, the Halliburton sales contact, doggedly felt it could still turn into a good investment. But it became necessary for both men to keep the company afloat financially, or it would close.

Their optimism was well placed.

Before long, the regenerated facility was selling increasingly more bentonite to the oil industry, not only to plug old wells but for necessary lubrication in well drilling.

So, fueled by the expanding auto industry and an uptick in oil sales – plus good luck and good management – a glued-together bentonite plant would eventually take hold and evolve from a ramshackle risk to a solid investment.

One of the attractions that immediately appealed to new customers was the Big Horn Mountain hunting opportunities east of Greybull and Yellowstone Park. Realizing this, the company purchased a hunting lodge and used it often to sate the appetites of present and future clients. It worked. Later came trout-fishing craft that entertained customers on lakes Yellowstone, Flathead, and Texoma (straddling the Oklahoma/Texas border.)

In January of 1952, Brown felt confident enough in his son Keith’s direction to gift his own shares into a newly organized family partnership (involving the four Brown offspring plus Dansby). He was soon leaving on an extended vacation and wanted to get this matter completed before his journey.

End of an Era:

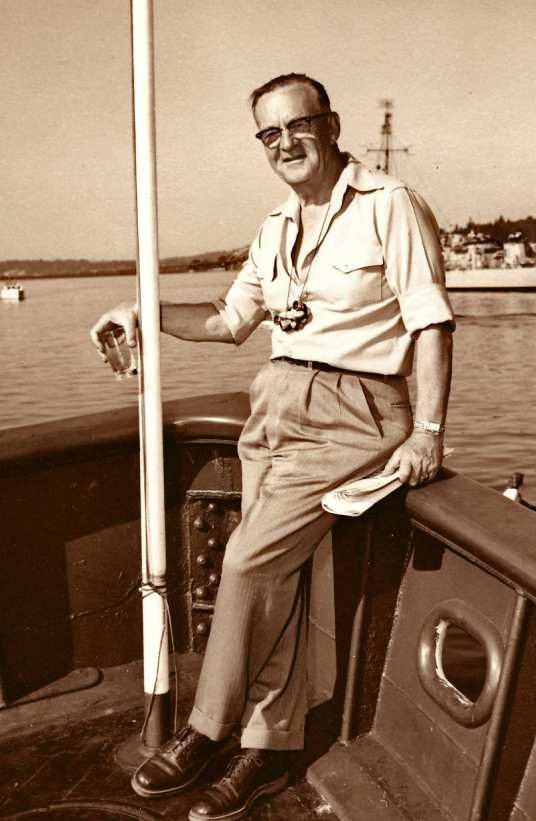

Death of Rockwood Brown

A news clipping announced the sudden death of Rockwood Brown on March 5, 1956. He and his wife were on a two-month vacation tour, visiting California and Mexico before arriving in Fort Myers, Florida, for deep-sea fishing. Rockwood suffered a heart attack there after having his morning coffee at their motel. He was taken to Lee Memorial hospital but did not survive.

Rocky and Keith flew down immediately to help their mother through the loss and make arrangements for her sad journey back home. Only a month before, on February 12, Rockwood had turned 69 years old. He had been a life-long smoker, but he had shown no other health problems.

While Keith accompanied his mom on the flight back to Billings, Rocky drove their car. Newspaper articles and mournful tributes awaited their arrival.

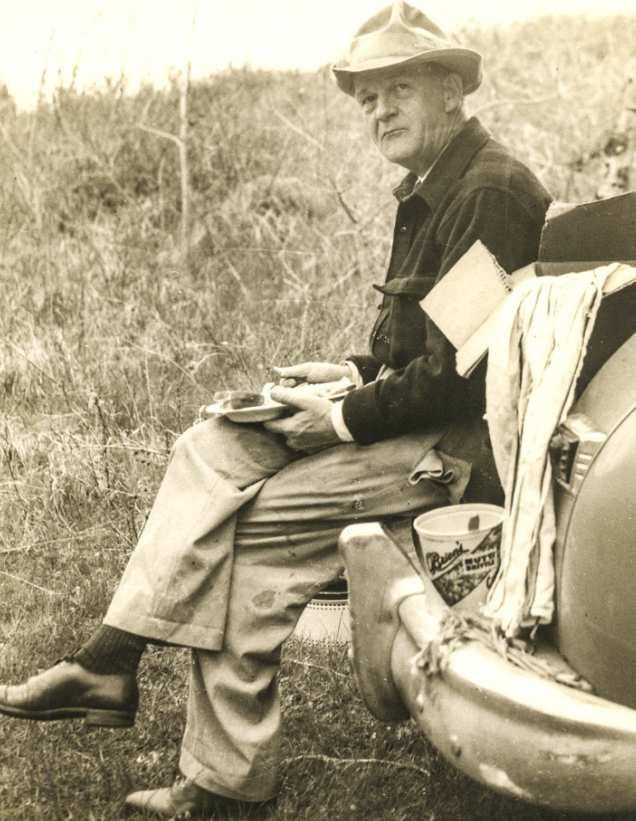

Although his name may not be recalled with other classic Montana natives like Charles Russell, Gary Cooper, Myrna Loy, or Chet Huntley, Rockwood Brown had a lasting impact on the state. He was not a Copper King, a high-profile governor, or an actor. But he consistently had so many different irons in the fire that he almost defied description. He had the drive and embodiment of an entrepreneur, willing to take on many risks while at the same time never pausing to note his successes. He set a positive model for any American life.

At the age of nine, he dealt with his father’s death and the precipitous change in his own daily life. Yet, he still excelled, graduating near the top of his high school, college, and law classes.

He took and survived many risks. Traveling 2300 miles from his birthplace to an isolated outpost in Montana, he set up and sustained a thriving law practice. He plunged into the hazards of entrepreneurship as though it was meant for him. He tirelessly served the state in high positions by forging many forward-leaning changes that still exist today. Serving his local community in similar leadership roles (including 26 years on the Billings Park Commission), he found time to promote the state and its resources. All the while, he nurtured a family that revered him as a father, never forgetting the people that guided him during his journey…especially his wife Elizabeth and his mother, Nellie.

And there was the future legacy of a company called Wyo-Ben, Inc.

Life Continues

In some companies, transition is sometimes set aside, leaving those organizations to lurch forward with little direction. Not so with Rockwood Brown’s ventures. Although his death was a shock to all, he had made adequate plans to carry-on his family businesses.