Pick Yourself Up

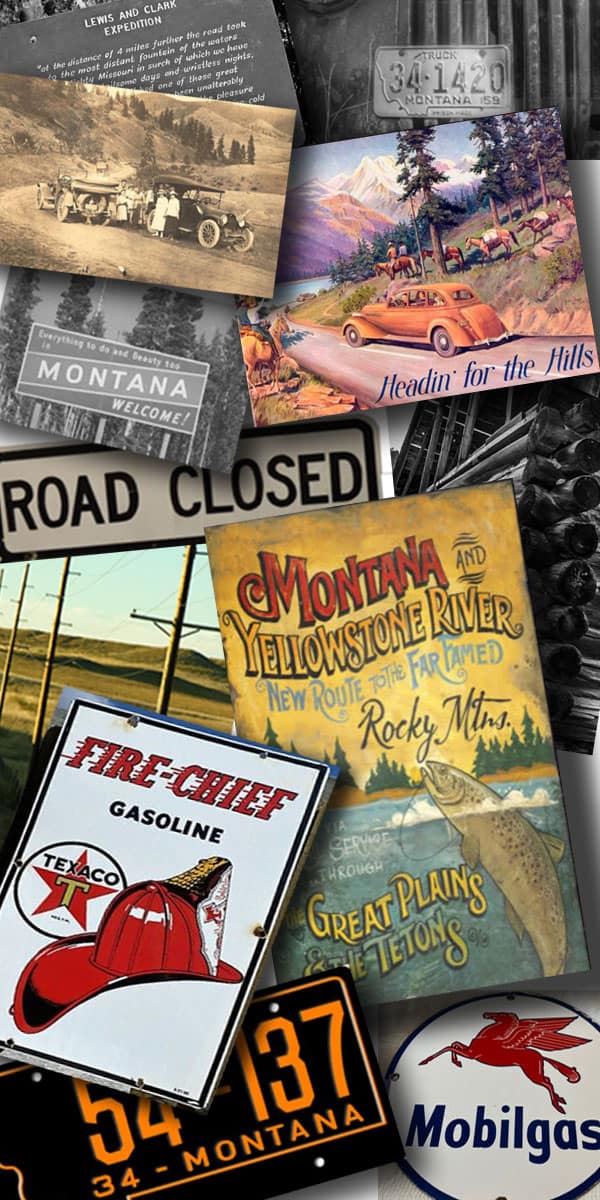

After 1929, Rockwood slowly started to regain his entrepreneurial composure. He had noticed a growth in Montana tourism, so he started two modern tourist campgrounds, first, a mile west of city limits on the Laurel Road and then across from the Midland Empire Fairgrounds main entrance. Both locations were called El Campo and sported cabins of 12 by 18-foot size, surrounded by grass and shade trees. The second location advertised a view of the Yellowstone River. Twenty-three cents per gallon gas beckoned tourists to Montana as tourism became one of the state’s top industries.

When they were being constructed, an interesting clay substance was used to seal the roofs of these cabins. This was Brown’s first introduction to a mineral called bentonite, a mineral that would come to have a great influence on his legacy.

Brown continued to build his sheep and sugar beet enterprise as he promoted Billings’ growth at every turn. His active involvement in Montana tourism did not go unnoticed. In 1935, Governor Cooney, looking for an eastern Montana representative, appointed him as one of two new members on the state’s Highway Commission. At 48 years of age, this assignment would thrust Brown into a whirlwind of activity and turmoil that would bring him even more notoriety in future years.

Governor Appoints Brown

If there had been time for Brown to recede into the background, now was the polar opposite. Elected to its vice chairmanship, Brown and the board quickly became a conspicuous center of state activity and statewide publicity. With a prompt from the Governor and acknowledgment that Montana tourism was a growth industry in its early stages, the new board members hit the ground running. They had ample state and federal monies supporting them.

If the public hadn’t yet heard of Montana’s potential as a tourist mecca, they soon would. The Going-to-the-Sun Road in Glacier Park had just been completed, and the new Beartooth Highway exiting Yellowstone Park would soon bring more travelers to Montana. In addition, colorful road names helped attract more visitors: the Glacier Trail, Custer Highway, Geysers to Glacier, and the Vigilante Trail.

Brown was always a vocal proponent of making the state more accessible for travel; now was his chance to do exactly that. Still, many residents had yet to understand that they sat on a gold mine of tourist sites. Even in the depths of the depression, Montana would see the highest road and highway construction activity of any state in the nation. At that time, the state was ranked third in area compared to other states.

While primarily focusing on Montana’s eastern half, Brown was also responsible for history-based tourist road signs and safety features that helped attract summer roadway visitors to Montana’s scenic majesty. In addition, with the rapid growth of vehicular traffic, he motored out weekly to speak before community groups about the need for resurfaced roads, new and upgraded highways, better signs, new routes, and ample support services. Newspaper and radio accounts attest to the frequency of his promotional trips.

New Building Sets Focus

Old Highway Department Building at Montana's Capitol

Federal funds strengthened the power of the highway department during Brown’s term and underlined the automobile’s importance to Montana tourism.

Although the board initially shared meeting space in the Senate Chamber and committee rooms of Montana’s beautiful State Capitol Building, a separate structure nearby was soon constructed to house its growing prominence and size. Inside the front door of the (old) Highway Department, there remains a plaque commemorating the building and noting Rockwood Brown as one of the three main galvanizers.

Its construction was not without its detractors. Still, these challenges were small-change compared to future events.

Oddly enough, Rockwood Brown would never occupy this building.