The Mustang Ramble

Regardless of his other business ventures, Rockwood Brown had never outrun his love of sports. He had always wanted to bring a minor league baseball team to Billings and had worked under the radar with other community leaders to do exactly that. Major League Baseball had finally approved the city’s application, and an executive committee acted quickly to further their approval. Anticipation grew.

In January of 1948, a public competition to select a nickname was promoted by the Commercial Club. The Billings Mustangs was chosen to carry the new team’s name.

Brown was elected the new club’s director, which welcomed 3280 baseball fans to its first home opener at Cobb Field on May 5, 1948. (Cobb Field, as of 2008, is known as Dehler Park.) The weather was despicably cold, but they played anyway. Welcome to Montana.

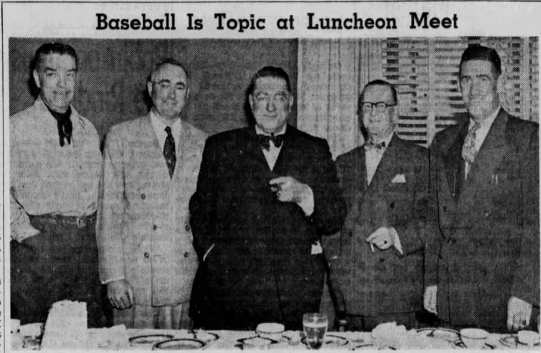

Both Brown and the late Grimstad had shared their passion for the game with another rabid baseball fan and former law classmate at the University of Michigan. His name was Branch Rickey. Rickey had become General Manager and partial owner of the Brooklyn Dodgers. The Cincinnati Reds had acquired the Billings Mustangs as a farm team, but nevertheless, Rockwood had remained close friends with the well-known Rickey and asked him to come out to Montana to help promote their new farm team. He did.

Not surprisingly, Rockwood, now in his mid-sixties, moved up to become President of the Mustangs, one of the most enjoyable and public positions he had held.

And On The Home Front

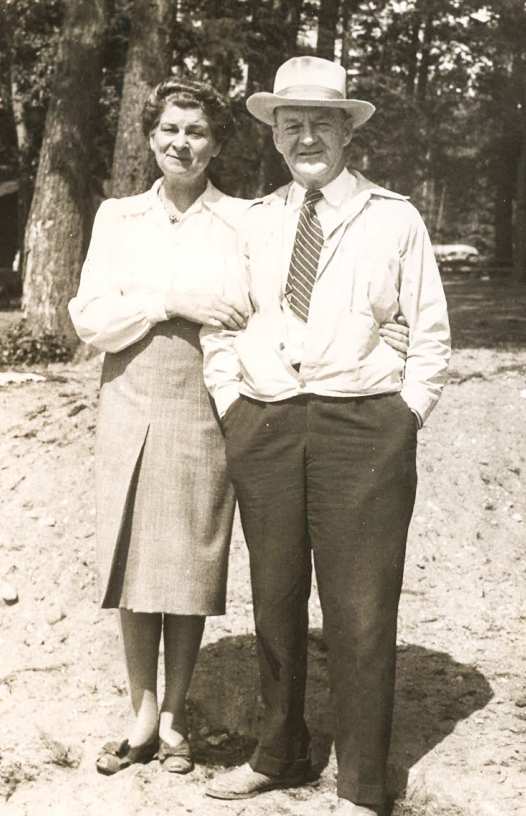

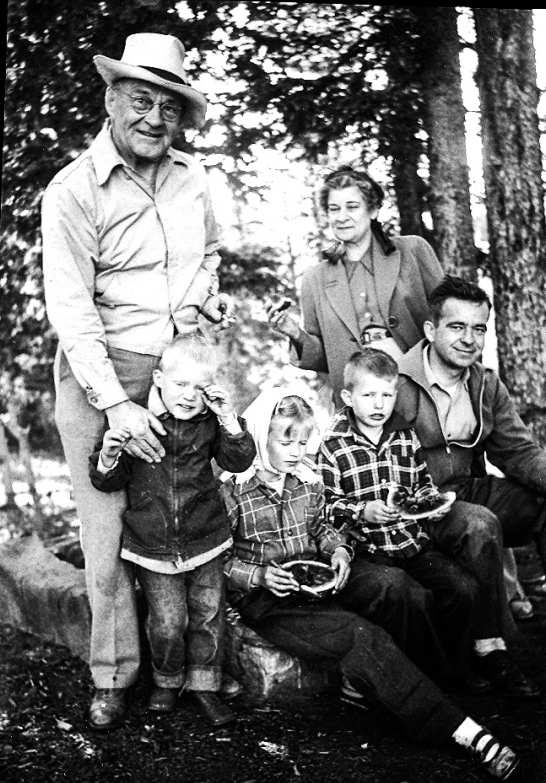

Rockwood’s wife Elizabeth was thrilled to see him remain in Billings once again. They always had a solid relationship, but she had been unsettled with his earlier need to drive around the state for countless speaking engagements. While gardening was her previous focus, now that pastime could take second-fiddle to more couple-filled and family activities. They were grandparents now, their boys were soon coming home from the war, and it was time to slow down.

Rockwood’s new executive position allowed both to travel to warmer climates for baseball’s spring training, to socialize and relax a bit more, bone-fish in Florida’s waters, and see some destinations they had little time for before.

There seemed a gradual change in Rockwood’s wish to control all his business interests.

New Leases On Life

At the moment, Rockwood’s concentration was on the Mustang Baseball Team. But he still retained ownership in other companies that grabbed his attention: Concrete Products, Roscoe Steel and Culvert, Inland Supply, two Gas Co-Op stations, and KBMY Radio.

Brown also owned part of a money-draining plaster plant near Greybull, Wyoming. In the mid-1920s, he had somewhat reluctantly accepted ownership in this small Wyoming production facility as payment for legal work. With it came a few mineral claims for gypsum, one of stucco plaster’s raw materials. Gypsum was already used at the plaster plant. But Brown was also given claims for bentonite clay, which was still relatively unknown and lightly used.

The early 1920s had seen a flurry of possible uses for this new mineral as a “de-inker” for newspaper print, a bug pesticide, beauty clay, and other obscure applications.

While supervising the state’s new water canals, Brown had noticed bentonite’s sealant properties. In fact, he had used it to coat roofs in his El Campo tourist units. So it had demonstrated minor commercial use. Yet, he had never acted on his own bentonite claims, which he guessed were still not economically viable.

In 1935, Rockwood regularly met with a cadre of nine prominent Billings entrepreneurs, who became known as “The Sheepherder Group.” Members of the group also owned a few Wyoming bentonite claims and wanted to know if they could become profitable.

Brown himself had no special knowledge of minerals or any background in strip mining. Even the U.S. government knew little about the mineral’s potential use. So, together, the Sheepherders decided to employ a geologist to determine the mineral’s current potential.

But it just so happened that the geologist they hired was also “in the pocket” of another group already buying up claims in Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin.

While sending a secret thumbs-up to this other investment group, the geologist discouraged Brown’s Sheepherders from spending any more time on what he suggested was “worthless speculation.”

As a result of his advice, nothing happened with these claims. For another 15 years.

But by the late 1940s, there had been too many positive notices about bentonite to ignore. The mineral was rapidly becoming a boon to Wyoming’s Big Horn Basin – the exact location where Rockwood’s claims had gone unused.

Maybe there was a future in this mineral after all, and maybe the geologist’s conclusions had been deceptive. Or wrong.

Take It Over

In October of 1946, son Keith returned from military service. He didn’t want to go back to the University of Michigan because he felt a preference for engineering over the law. So the younger Brown researched Billings opportunities instead. When he found few openings, his dad pointed out that he owned 50% of a business called Concrete Products, which was not doing well financially. Keith would probably be interested in helping that company survive…yes?

Rockwood’s forceful personality and immediate need for help had pre-determined the answer.

He again “strongly encouraged” his son Keith to make the Stucco Gypsum Plant, near Greybull, profitable…

…and by-the-way, he should determine if bentonite could be successfully mined in quantity…

…oh, and one more thing. There were these other businesses that needed management.

This was the last time Rockwood Brown would need to “strongly encourage” his son’s business sense to guide him. Keith Brown assumed responsibility for managing his father’s other businesses. And after confirming the potential economic benefit of bentonite, he needed little prompting to move forward.

Another son, Neal, also returned safely from the war. He married and lived for 12 years in Rhode Island before migrating back to Billings with his wife and daughter. Although Neal joined Keith at Concrete Products, which he later managed, he really wanted to open his own fiber-glass business. By the late 1960s, Neal did exactly that and often provided ingenious solutions for the Brown businesses.

A Puzzle Resolved

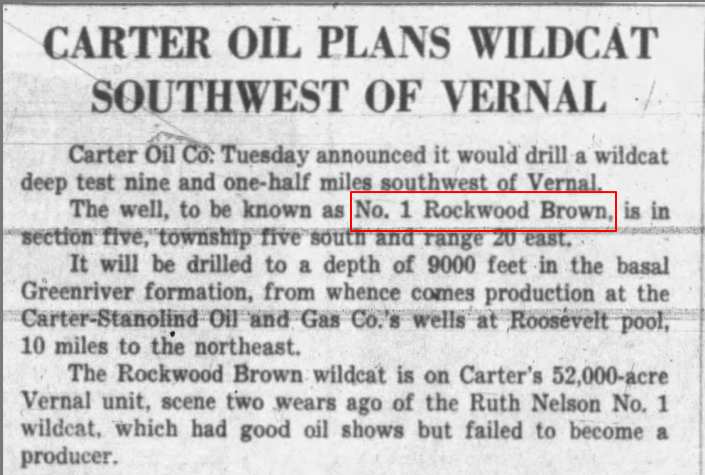

While Rockwood was slowly divesting himself of obligations, a strange article appeared in a Utah newspaper. In December of 1950, an oil well south of Vernal, Utah, was being drilled using the name No. 1 Rockwood Brown, and newspapers of the state eagerly reported on its drilling. It so happens that the owner of Carter Oil (Vincent Carter) was a satisfied client of the Brown law firm, and the lease would later be offered to Mr. Brown himself. Unfortunately, the well was eventually abandoned as non-productive, though newer and deeper drilling methods have made it once again active today.

Concrete Products

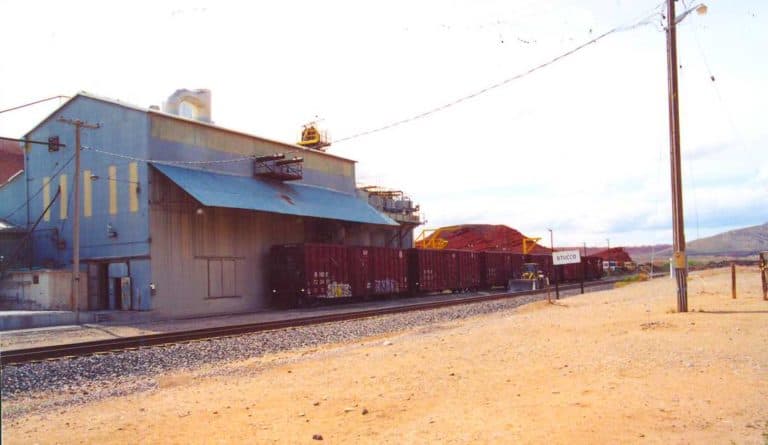

In the early 1950s, Concrete Products Inc. survived on a meager margin by running daily classified and display ads to publicize its lightweight building products. In 1955, the “Block Plant” as it was known, moved to its Hesper Road location. The business had shown gradual promise and Keith was ramping it into stability.

Events of Significance During the Period: 1949- 1954

1949 – Joe Louis Hangs Up Gloves

1950 – Flying Saucers In The News

1950 – Lowest Temperature Ever Recorded in U.S. -70 Degrees Rogers Pass, Mt.

1952 – McCarthyism Runs Rampant

1953 – Marilyn Monroe on Playboy Magazine Cover

1954 – Salk Polio Vaccine

1954 – “Separate But Equal” Struck Down

Inventions and Fads: Charlie Brown Comics, Sugar Pops, Smokey Bear, Sugarless Gum, Power Steering, Roy Rogers, Push Button Garage Doors, Vibrating Mattresses, Motorized Lawnmowers, TV Dinners, I Love Lucy, Scrabble, TV Guide, Crew Cuts